By JAMES CHENEVIX-TRENCH

By JAMES CHENEVIX-TRENCH

In this article we discuss the nascent industry of alternative protein.

We put this industry in its global and historical context and break it down to give a full picture of the scale and nature of innovation in the space. Further to this, we seek to give a broad view of the challenges, bottle necks and limitations that this new industry faces and explore ideas about its transformative potential.

There is no industry on Earth more important than food production. The farming of crops and animal husbandry has led to the experience of our environment as malleable, optimised for the benefit of humans. Rivers, once powerful natural realities, could be diverted to transform a desert into a productive field. Cattle, once wild animals hunted over vast areas became a resource that could be developed to produce reliable quantities of meat and milk, or even persuaded pull a plough. Despite the vast change in power over their environment that began some ten thousand years ago, human beings have changed very little in that time. Following millions of years of evolution we have the same nutritional requirements as our ancient ancestors in Mesopotamia and the same desires and flaws. Since the agricultural revolution humanity, has further optimised the primary production of food, but has also developed complex manufacturing techniques, creating entirely new food products to better serve our nutritional needs or to sate our desires for certain types of food. Today, the global agriculture sector can produce many more calories than the aggregate world population requires. Our move from gathering food at the mercy of nature to controlling a surplus is complete. What is still open for change is the types of food we decide to produce and consume and the environmental, health and ethical implications of those choices. Across the world there are now great differences in production techniques, resource allocation and animal welfare standards, as the process of efficient food production develops. There is a nascent shift in the allocation of resources away from the production of meat and dairy to alternative sources of protein. This could be the most significant change in the primary and secondary production of food since the domestication of plants and animals.

Peak meat

If an extraterrestrial observer were to peer down at our planet and count the numbers of large animals inhabiting its surface, they would find 7.9bn bipedal apes, 26bn chickens, 1.5bn cows, 1.2bn sheep and 677mn pigs. In many geographies these creatures would outnumber humans. The alien observer could therefore be forgiven for being confused as to which species truly dominated the Earth. Further inspection would present them with facts. It would become clear that the chickens, cows, sheep, and pigs exist for the benefit of humans’ practice of eating their flesh and harvesting their milk. In 2020 humans ate an estimated 574 million metric tons’ worth of meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs: equivalent to almost 75 kilograms per person[1]. This number continues to grow, led by demand from the developing economies. As the global population has grown and incomes have increased, so has the tonnage of animal protein consumed.

Despite these stark numbers, signs are building in the developed world that we might reach the zenith of this demand or ‘peak meat’[2], the moment when demand for animal-derived protein begins to decline for the first time in human history. For now, these trends are manifesting themselves most strongly in the western developed world. A mix of changing attitudes and advancing technology is enabling this shift. On the one hand concerns about the environmental costs of raising the animals we eat, differences between welfare standards around the globe, and scrutiny of the health impacts of eating such large quantities of meat, are receiving greater attention. At the same time new technologies are being developed to meet demand for alternative sources of protein. The consequences of any shift to alternative proteins are potentially far reaching.

The Rise of Alternative Protein

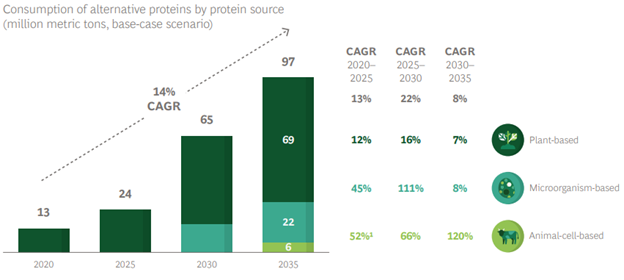

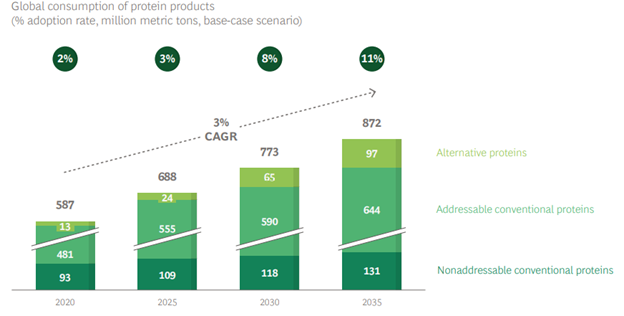

The growth of the market in alternative protein has been significant in recent years notwithstanding a recent slowdown in sales. Over the last five years the alternative protein market has emerged from close to zero to a value of US$14bn and growing at a compound rate of 50% per annum across that period. While the global market for alternative proteins as of 2021 represents only a small fraction of the traditional protein market (the global meat market and dairy markets are currently valued at around US$1.2tn and US$0.8tn, respectively[3]). At the current rate of growth, alternative proteins will make up 11-22% of all protein consumed by 2035.

As laid out in a recent report from Boston Consulting Group (BCG)3, the growth in alternative protein can be broken up into three distinct technologies:

- Plant-based (foods that are produced from plants and can be substituted directly for conventional animal-based products, such as meat, seafood, milk, eggs, and dairy. Traditional plant-based foods such as pulses, tofu, are excluded from this definition),

- Micro-organism based (foods based on microorganisms including fungi, bacteria, yeast, and microalgae that are grown in a bioreactor)

- Animal cell-based (refers to foods based on animal cells that are grown in cell cultures, starting from a small number of cells taken from a live animal).

Three types of alternative protein

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Source: Boston Consulting Group

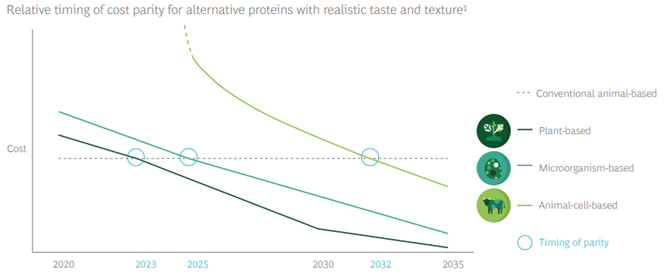

Moo’s law and ‘Griddle Parity’

In his book ‘Moo’s law’, Jim Mellon, a fund manager, describes the marriage between technology and a new agrarian revolution that will involve alternative proteins achieving ‘griddle parity’[4]. Mellon is drawing a deliberate comparison with Moore’s law (the rule that semiconductors double in processing power every 2 years) and grid parity (a term to describe the moment renewable energy becomes competitive with fossil fuels). From this framing Mellon draws an interesting insight based on the application of technology to scale production of alternative protein.

Mellon believes there is no reason why alternative protein cannot be cheaper, tastier, and healthier than conventional meat and unlike live animal farming, it can keep improving, much like the silicon chip. In contrast, meat and dairy products have essentially remained the same since the agricultural revolution. The conditions needed for alternative protein to replace traditional protein will arrive when alternative protein has reached equivalence in taste, texture, and price with conventional animal proteins. Currently, plant-based protein, in the most part derived from soy and peas, is closest to reaching this milestone.

The companies Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods are leading the way towards ‘griddle parity’ particularly in their ‘ground beef’ products. Today you can find Beyond Meat’s plant-based products in supermarkets, restaurants, and fast-food chains such as McDonald’s, and Pizza Hut. As of 2021 the cost of plant-based alternative protein is still greater than the cost of conventional animal protein. However, the gap will continue to narrow if these companies can optimise processes and scale up alongside growth in demand. Current work aims to improve sourcing for production at scale, while improved extraction, formulation, and texturising will be required to significantly reduce costs.

Reaching ‘griddle parity’ on three fronts

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Source: Boston Consulting Group

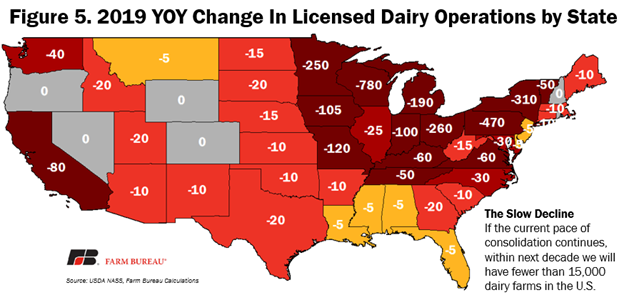

The dairy industry

The first signs of seismic change might be evident in the US dairy industry. Today milk alternatives can be found in over 40% of US homes. This is forcing bankruptcy in dairies not able to consolidate. Should profitability continue to be squeezed out of milk and meat production, even the consolidated entities may not be immune to the shift. The latest year with USDA data available, starkly illustrates this decline. In that year more than 3,200 dairy farms shut down. From 2003 –2019 the same data reveals that the number of dairy farms licensed to sell milk has declined 50 percent from 70,000 to just over 34,000 in 16 years. Multiple factors have driven profitability from primary production, not least the attraction of cheap food to governments seeking social stability and the bargaining power of retailers. However, a growing demand profile for alternatives to milk has added another pressure to the dairy farmer and will change supply lines significantly.

Source: USDA Farm Bureau

The dairy and beef industries are intimately connected. Disruption from alternative milk is being matched by disruption from alternative protein. The shift is so dramatic that when these trends are forecast into the future, some analysts are predicting the widescale destruction of the US cattle industry as we know it by 2030[5]. This view is illustrated by some stark numbers in a paper published by market think tank Rethink X which forecast demand for cattle based products in the US falling by 70% by 2030[6]. This may be an extreme prediction, but even if it only partially holds, significant change is taking place.

Resistance and headwinds

The possible disruption of a large established industry will face resistance. The recent history of renewable energy versus fossil fuels may provide some useful comparison. Renewables initially faced huge resistance from the established oil and gas industry and have battled against governments often under the influence of these established players. Nevertheless, the march of technology has been inexorable and today the same companies that lobbied the US congress to curtail generous subsidies of wind and solar are now the largest investors in those same industries. When reviewing the predictions of analysts like Rethink X we should keep in mind the barriers and bottlenecks that will shape the growth of alternative protein as these headwinds will tell us something of how the industry might develop.

Falling sales and hype cycles

In a recent article for the FT [7] the writers lay out the state of current demand for alternative protein. The COVID-19 pandemic created a boost for alternative protein products. Stuck at home and facing recurrent lockdowns, Western consumers were more prepared than ever to try these products, at a moment when they were hitting the shelves at enhanced scale. This was in the main thanks to advances in scale production from Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. However, a 46% rise in sales in 2020 has been met with a 0.5 % fall in 2021. The slowdown in sales growth has negatively affected the share price of the largest plant-based food company Beyond Meat. Beyond Meat was listed on the NASDAQ in May 2019 at US$25/share. Its share price peaked in July of that year at US$239 and as of 02/03/2022 trades at less than US$45/share.

This sales slowdown may be best explained by the ‘Gartner hype cycle’ of emerging technologies. This charts the five phases in the lifecycle of a new technology; an initial surge in expectations and then disappointment when it does not fully deliver, leading to consolidation or company failures, improved product, and finally mainstream adoption. Following the initial growth of alternative protein products, we are now in a period of disappointment with current product in terms of taste and health benefits, and a vast increase in the number of customers now familiar with these products. This represents a critical juncture in any journey towards largescale acceptance.

Investors who are committed in the space do not see this slowdown in sales as a long-term trend, indeed views from industry experts are aligned in seeing this as a bump in the road to further product development and consumer adoption. Hanneke Faber, President of Unilever’s foods division, sums up these views when she says that she believes that the US phenomenon is temporary and predicts that “going forward this market will continue to grow in the 20 per cent range”[8] every year.

Nutritional concerns

Critics of alternative protein products in the plant and microorganism categories point out that they are highly processed. Meat and dairy from animals, contain all the essential nutrients and amino acids that humans require from their protein intake while, in contrast, current alternative protein products are complex and should be treated with skepticism in their nascent stage. An examination of the most popular products such as the Beyond Meat burger give some validation to these concerns. The main ingredient of Beyond Meat burgers are yellow peas, they also have juice additives for texture, colorings to mimic the look of meat, nutrient additives like zinc, flavorings to give an umami taste, and crucially the binding agent methyl cellulose to hold the patty together. Methyl cellulose does not occur in nature and must be produced by heating cellulose with a caustic solution like sodium hydroxide, it is often used in ice creams and as a thickening agent in shampoo. While the long lists of processed ingredients on the packaging of alternative protein products may put some consumers off adoption, current studies give a more nuanced picture of the health benefits of these products. Research funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health found that imitation meats are a good source of fiber, folate and iron while containing less saturated fat than ground beef. However, they also contain far more salt than ground beef. For comparison a typical four-ounce beef patty has about 75 milligrams of sodium, compared to 370 milligrams of sodium in the Impossible Burger and 390 milligrams in the Beyond Burger. Plant based alternative protein products contain this volume of salt for reasons of flavor and to imitate meat more closely. Alternative protein products will have to do more to get nutritionists on side. It is worth noting that alternative milk and dairy products have largely achieved this, and it is not beyond reason that other alternative protein products could get there too.

These issues exhibit a different cross section to the debate, that which identifies food of all types as natural, processed, and ultra-processed. To qualified nutritionists, a natural pea would be that which is shucked from a pod in its raw form. If it were heated and mashed into a paste, it would qualify as being processed. If it is incorporated into an alternative protein burger with the above listed ingredients, its forms part of an ultra-processed product.

Scaling challenges

Today the largest volume manufacturers of alternative protein are in plant and fermentation technologies, but even the largest of these volumes are very small when compared to the traditional meat industry. The more speculative startups in alternative protein tend to see themselves as tech companies in a space that is all about volume manufacturing and this represents a significant barrier to reaching parity. For example in a recent industry summit[9] on alternative meat, fermentation specialist Meati Foods announced plans for a ‘ranch’ capable of producing 30 million pounds of alternative chicken per annum. This would be one of the largest fermentation facilities in the US and yet this is enough product for just one large national contract. To make a serious impact the company will need a facility ten times larger. To reach parity in price, alternative protein companies will need vast new infrastructure to produce at sufficient scale.

Texturisation challenges and the quest for whole cuts

The challenge of scaling in alternative protein is exacerbated when it comes to replication of whole meat cuts. It is unsurprising that parity is hardest to achieve in things like marbled beef steaks and other whole cuts with complex variable textures (Tuna steaks are easier). In the United States whole cuts make a significant proportion of the traditional protein market and as a result dozens of alternative protein companies are focused on aspects of reproducing the taste and texture of whole cuts. Most alternative protein companies lack the production facilities associated with meat product manufacture, while some ordinary extrusion processes that create meat-like fibers have been found to be unsuitable for creating alternative fish products and whole cuts. To achieve parity therefore, entirely new manufacturing processes must be invented to produce whole cuts at scale. The texturisation and manufacturing challenges present a bottleneck for the alternative protein industry that can only be ameliorated by specialists who can provide expertise in manufacture, texturisation and flavours to alternative protein companies. This picks and shovels dynamic is already happening; notable companies include Umiami (texturisation specialist working with Quorn) and Aromyx (flavour and aroma specialist).

In plant and fermentation-based technology, taste, texture, and nutritional parity are like a complex balancing act where an improvement in one category can produce a deficit in the other. This is not true of cultivated meat. Here the closer researchers get to the real thing the closer they move toward parity on all fronts and here the future holds the promise of parity in even the most complex whole cuts.

Government regulation

The growth of alternative protein requires favourable government regulatory systems to thrive. Currently Singapore is the only country to allow the sale of cultivated meat to consumers, and there is resistance from meat producers to even less speculative plant based products as witnessed by the recent arguments in the European Parliament over the right of alternative protein companies to call their products milk, sausages and burgers.[10] Compared to renewable energy, alternative protein technology has lower startup capital costs – however it will still need a fair regulatory regime if it is to compete with the traditional meat industry.

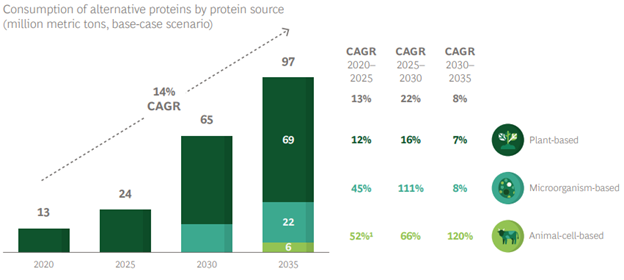

The future of the future – ‘Clean meat’

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Source: Boston Consulting Group

As seen in the chart above, so-called ‘clean meat’, (that is ‘cultivated meat’ or animal-cell-based protein), is projected to only make up a small fraction of the alternative protein market by 2025. When speaking with venture funds and entrepreneurs in the space it becomes clear that most believe that cultivated meat is too early in its development for most investors and scale production is a long way off. Currently meat is cultivated in bioreactors originally designed for the pharma industry – to be produced at scale, purpose-built bioreactors would have to be developed. However, it is still set to become the fastest growing segment of the market. Distinct from plant-based or microorganism based alternative proteins, clean meat is produced from cells extracted from a living animal. The cells are then cultured in a lab in a special medium and persuaded to grow into animal tissue. This is true science fiction and offers the chance to effectively grow a chicken breast without a raising a chicken.

On 19 December 2020, lab grown chicken nuggets were sold for the first time in a restaurant in Singapore. These nuggets were made by Californian company Eat Just (better known for its plant based scrambled eggs) and it was the first time in human history that meat that not derived from a slaughtered animal has been sold commercially. Unlike other alternative proteins, this was not a substitute, the nuggets had been cultured from cells in a bioreactor. The cultured chicken meat was approved a few weeks earlier as fit for human consumption by the Singapore Food Agency, the first and as yet, the only time a regulatory regime anywhere in the world has authorised for human consumption meat that did not come from animals.

Eat Just is not alone in the race to produce ‘clean meat’. In the last two years dozens of companies have joined the race to produce cultivated meat at scale. Notable examples include an Israeli company SuperMeat that is close behind in producing lab grown chicken, while in the UK Oxford startup Ivy Farms is attracting funds to produce cultured pork sausages. If you prefer fish, then Blue Nalu is seeking to lead the world in cultured sea food.

It is important to remember that this is a nascent space. The cost of making clean meat is still many times more expensive than farmed animal protein under either intensive or extensive regimes, but the promise of this technology cannot be underestimated. In the next agricultural revolution, we might move from farming animals at factory scale to a factory farm without animals. Imagine a large farm, with multiple bioreactors next to one another, like cows in a barn. To some, this may raise the question of the source of manure for maintaining the healthy soils required to grow plant-based protein.

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Source: Boston Consulting Group

Investment opportunities

Although the pandemic was the moment alternative protein broke into the mainstream this is still a nascent industry with few opportunities for investors represented in public markets. In private markets it is also challenging to find a way in, the entire area of ‘cultured meat’ represents next generation technology that is simply too premature for most investors. This reality is confirmed in recent conversations with aggrotech venture funds where they emphasise, that although they are keeping a close eye on cultivated meat, they prefer to focus on fermentation and plant-based technologies.

Beyond Meat remains the only large, quoted company focused purely on alternative protein, and is now facing headwinds as they grapple with changing market conditions and the realities of volume manufacturing. The best way to gain exposure to this emergent technology is in the companies that will provide the picks and shovels to this shift and those that are structurally advantaged to benefit from the move to alternative protein. Alternative protein companies will have to achieve scale manufacturing to achieve parity with traditional meat products, getting there is going to involve the design and production of new manufacturing processes. Companies like GlaxoSmithKline and Thermo Fisher are likely to play a role in the development of commercial bioreactors for animal cell and microorganism cultures. Plant based foods require extrusion and 3D printing specialists to mimic the feel and texture of meat. It is likely that some companies will be able to provide vital ingredients to the alternative protein industry like Hoxton Foods, a startup focused purely on producing fat cells to achieve a juicy taste and texture on par with the best traditional meat products. The complex list of ingredients on the back of a box of Beyond sausages are testament to the amount of R&D that has gone into achieving an authentic flavour and the need for flavour specialists. Established food giants like Nestle, Unilever and Tyson Foods are investing in the space to exploit this new market and these structurally advantaged companies may well become ultimate beneficiaries of the shift to alternative protein particularly if they can mitigate the disruption to their established businesses.

Looking to the future

Despite the challenges facing this nascent industry, its disruptive potential is clear. We must think about what the developed world will look like beyond peak meat. If bullish predictions[11]on alternative protein are close to accurate – we can expect that around 60% of the land currently being used for livestock and feed production in the US will no longer be used for these purposes by 2035. This area represents one-quarter of the land in the continental U.S, that is almost as much land as was acquired during the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The implications of so much land being managed for other purposes would be seismic. The promised benefits of alternative protein in its ability for constant improvement could have a profound impact on human health, both in a reduction in foodborne illness and in possibly in helping alleviate diet related morbidity. These promises must be set against nutritional facts which may be misrepresented by the drive to market commercialised alternatives. Further to these impacts there are environmental expectations; alternative ventures are expected to deliver reduced greenhouse gas emissions and improved habitat management. Imagine the possibilities of rewilding the Great Plains and creating vast carbon sinks? The shift to protein alternatives has the potential to be transformative, and the change will not come without cost for those involved in the traditional meat and dairy industries. Like all disruptive changes, this will not be a smooth road, however a direction of travel has been mapped. In going down this path humanity will be on its way to achieving the latest phase of mastery over our food environment, a mastery that began with the domestication of crops and animals and now promises a command over chemistry and genetics that could lead to a new agricultural revolution.

—

[1] Boston Consulting Group ‘Food for Thought: The Protein Transformation’24/03/2021, P.1

[2] Ibid P.20

[3] Ibid

[4] Moo’s Law: An investor’s guide to the new agrarian revolution, Jim Mellon, 2020

[5] Rethinking Food and Agriculture, Rethink X, 09/2019, P.2

[6] https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2019/09/17/

[7] Financial Times, Has the appetite for plant-based meat already peaked? Emiko Terazono and Judith Evans, 27/01/2022

[8] Financial Times, Hanneke Faber, 27/01/2022 – https://www.ft.com/content/996330d5-5ffc-4f35-b5f8-a18848433966

[9] Future Food Tech Summit, 22/06/2021

[10] Sky News, ‘Meatless plant-based products can still be called sausages’, 23/10/2020 – https://news.sky.com/story/meatless-plant-based-products-can-still-be-called-burgers-and-sausages-eu-rules-12112315

[11] Rethinking Food and Agriculture, Rethink X, 09/2019, P.8