By MICHAEL FLITTON

For investors familiar with placing funds in commodity markets, awaiting the structural deficit in copper has felt like being a participant in Zeno’s ‘Achilles and the tortoise‘ paradox.

At each previously identified tipping point, events conspired to move the target again, seemingly forever just out of reach. However, this dynamic may be about to change. The global, concerted effort to transition towards renewable energy introduces a new structural demand factor, which may tip the market into persistent tightness. Such conditions point to a broadly rising pricing environment prone to sudden, sharp spikes. Exposure to this dynamic could be valuable within a multi asset context. In this note we address the challenges of supply, the demand picture, and implementation within portfolios.

Supply challenges

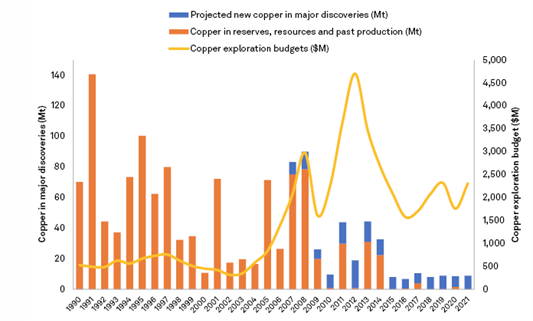

Copper supply has tended to underwhelm due to chronic challenges in discovery and extraction. Following the end of the super cycle in 2008, these challenges were exacerbated by a concerted aversion to capital expenditure on the part of the mining companies. The mechanics of mine development, where greenfield flash-to-bang is 7-10 years, mean we can gain a good understanding of how long the situation will take to rectify.

There are a range of factors at play stymying supply.

- New mine permitting. Environmental regulations have become increasingly stringent for new mine development. Local communities have long opposed projects but the global increase in awareness around environmental issues has led to rising sensitivity from authorities. Overall, 50% of the projects analysed by Goldman Sachs have seen production starts delayed by 3 years or more.

- Reduced quality of copper deposits. Copper grades have been falling for some time as miners first prosecuted the highest potential opportunities. 150 years ago, open pit grades were 5%, now they are 1%. That means mechanically 5 times the quantity of ore needs to be extracted for the same copper unit. Since 2005, Chilean copper mines have had to double investment just to maintain the same level of production[1]. These additional costs impact mine economics and reduce the likelihood a deposit will be developed.

- A reluctance to spend. The mental trauma following the excesses of the super-cycle should not be underestimated. During the 2003-2008 period, capital expenditure at mining companies surged as CEOs, flush with cash, rushed to build into the never-ending demand from China. When the music stopped, shareholders were left holding the can. Since then, investors have installed management aligned with their priorities of harvesting asset value through dividends. The copper price has also been weak, only in 2022 has it regained spot pricing of 2011. As a result, only low-risk brownfield projects have been sanctioned. Pursuit of large scale, greenfield projects, which costs billions of dollars and take more than a decade to pay back, has been put on hold. Only 3 mines have been discovered in the past five years[2] with the majority of new reserves from older, well-developed discoveries.

Source: S&P Market Intelligence

Secular demand

From a demand perspective, copper holds an integral, hard to substitute role in economic activity. This is a function of its specific conductive properties. At prevailing cost levels, there is no better conductor of electricity. Aluminium can be used but its conductivity is weaker so 2-4x more metal is required limiting its use cases, particularly in miniaturised electronic settings. Silver is more conductive but is 90x more expensive. Copper represents only a small cost of the overall product but is vital for its functioning. Therefore, we can describe demand as generally inelastic.

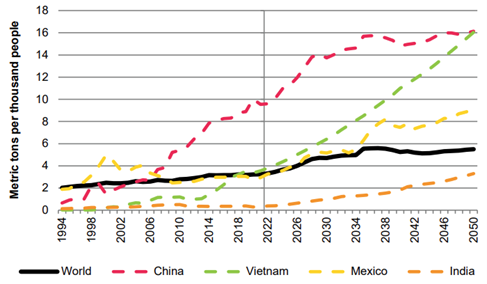

The historic demand for copper is tied to industrial activity but with a rising level of intensification over time. This is a function of the rising incomes and the electrification of economies.

Refined Copper Consumption Per Capita

Source: ICSG, S&P Global

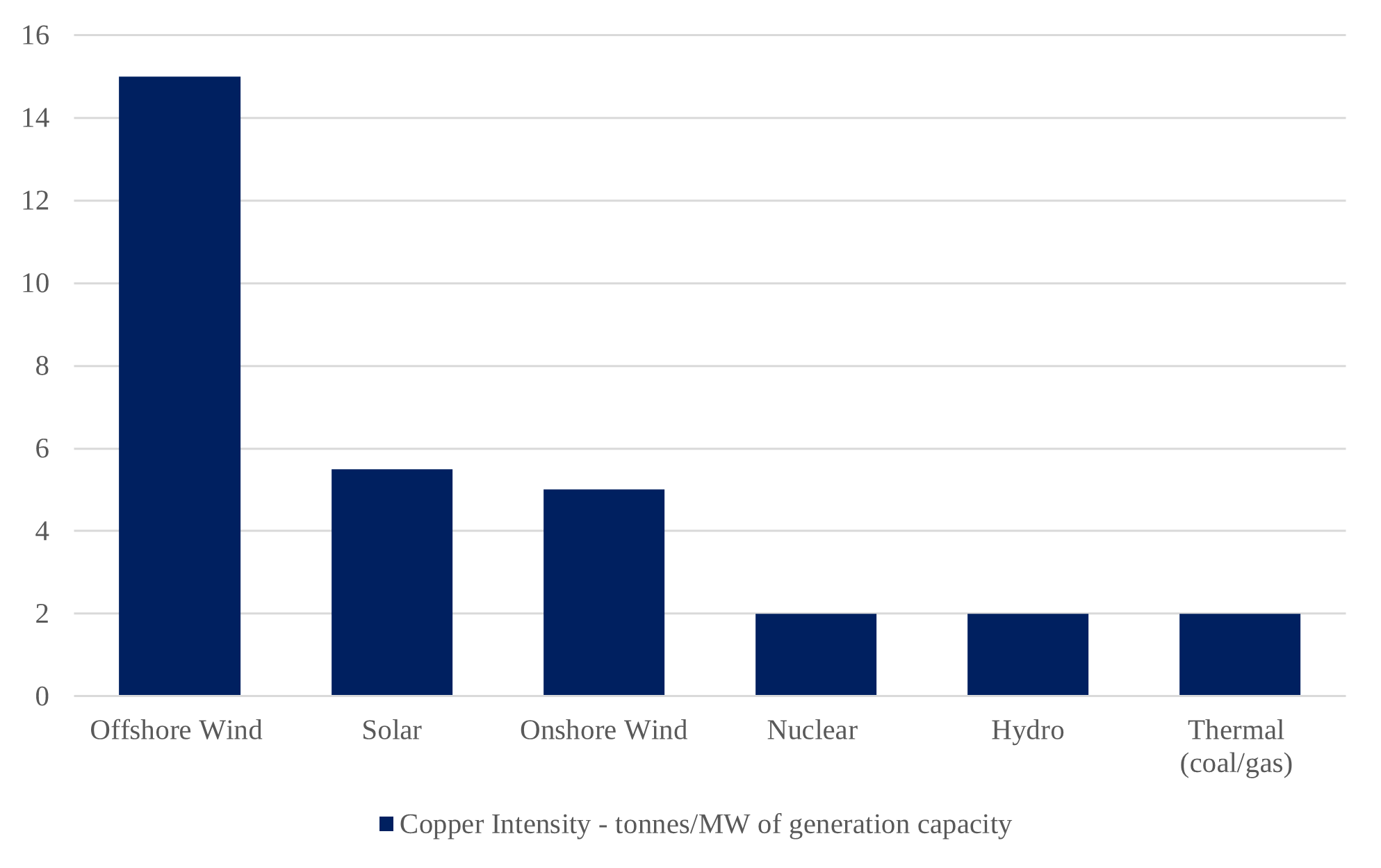

On top of this base level demand is the incoming impact of green transition demand. Electrification is the functional outcome of the world’s attempt to move away from fossil fuels and towards renewable sources of energy. Copper is therefore involved in almost all aspects of this shift. The transition will result in a gear shift in copper demand given renewable capacity is far more copper intensive than fossil fuels. This also applies to the demand side where electric vehicles can use up to three and half times more copper than a petrol car[3].

Copper Intensity of Electricity Generation by Type

Source: UBS

Source: UBS

As a result, S&P sees global copper demand doubling by 2035. Within this, ‘green’ demand is forecast to rise from 4% today to 20% by 2035. Assuming steady global economic growth, existing non-green demand is likely to remain robust.

There is one threat, a known unknown at this stage. Residential construction in China represents c13% of China demand and 8% of global demand. There is little visibility on the recovery profile for the sector and demographics are tilted heavily against it. Most analysts assume a continued attrition of property demand of c1% per annum. If these estimates prove significantly too optimistic, then this could be impactful to the market balance.

Deficit emerging: this is not a drill

A structural copper deficit has been expected for years. However, brownfield capacity has always been able to rise to meet these shortfalls. The energy transition has the potential to change the game as it overlays new secular demand on top of the existing industrial use case. If we accept the demand forecasts, the amount of copper required between 2022 and 2050 is more than all the copper consumed in the world between 1900 and 2021[4]. This prospect may alter the historic balance in copper allowing us to view the prospect of an open-ended deficit with less circumspection.

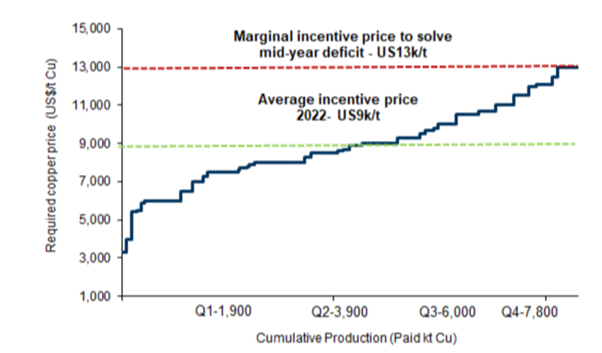

What does this mean for price? Simplistically mining companies need to deploy $150bn of capex to plug the 8mt gap. At today’s prices the resource in the ground is not economic to extract. Thus, the economics need to change. To bring on a new project requires copper at US$13,000/t (US$5.9/lb) rising to US$15,000/t (US$6.8/lb) by 2025. This is 55-78% above spot.

Source: GS

Source: GS

The geopolitical grey swan

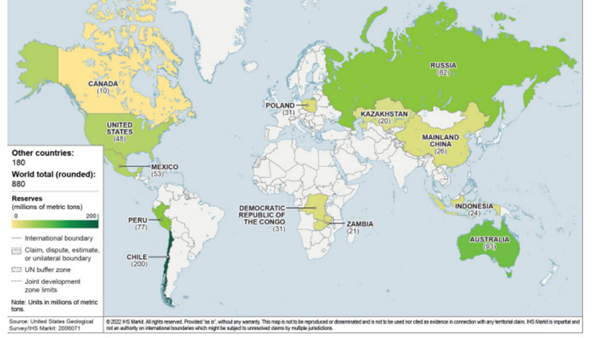

The nations supplying the world with the critical metals for the green transition are waking up to the power of their hand. Copper is a relatively common element within the earth’s crust but the distribution of economic deposits is not equal.

Copper Reserves 2021

Source: S&P Global

Source: S&P Global

There is an even greater imbalance of processing capacity. China accounts for only 8% of copper production but over 50% of global demand. The Chinese authorities have worked to ameliorate this mismatch through acquiring global mine assets as well as building refining capacity. Today, China accounts for 40% of refined copper production. Given this set up, it is conceivable that an informal (or formal) cartel could take shape in the next 5 years. Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel producer, has already publicly floated the idea. Geopolitics therefore presents asymmetric upside risk for copper prices.

In conclusion

The time may finally have come for the next prolonged cycle in copper. Given the economic crosswinds in 2023 the path for prices is unlikely to be a linear one. History also teaches us to be sceptical of fabled deficits in copper. Nevertheless, the size of the mismatch now looks compelling, even if not fully realised. Behavioural factors are also supportive. The mining CEOs remain disciplined. When they ‘lose religion’ and press the capex button we will know the initial phase of the bull market is over.

Within our multi-asset strategy, copper has a role to play as a diversifier and sits alongside other opportunistic positions, including European Specialty Chemicals.

[1] Volt Rush, Henry Sanderson

[2] S&P Global Market Intelligence

[3] Volt Rush, Henry Sanderson

[4] S&P Global