By OSCAR MACKERETH

“For things to remain the same, everything must change”

“Se vogliamo che tutto rimanga come è, bisogna che tutto cambi”

Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa- The Leopard/Il Gattopardo

Introduction

In the equity strategies that we run we look for innovative, market-leading businesses with adaptive and forward-thinking management teams. We aim to capture value as these companies adapt and exploit their competitive advantages.

The issue of the age is the global response to the climate crisis. In the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global risk report[1], four of the world’s ten most likely risks, and five of the ten most impactful risks are environmental risks, linked to climate change, namely:

- Extreme Weather – Most likely and eighth most impactful

- Climate Action Failure – Second most likely and second most impactful

- Human Environmental Damage – third most likely and sixth most impactful

- Biodiversity loss – Fifth most likely and fourth most impactful

- Natural Resource crises – Fifth most impactful

In this report by Oscar Mackereth, we summarise the path from the Paris COP-21 of 2015 when a maximum warming of 1.5% was first laid down and the more recent Glasgow COP-26. We look at how Cerno Global Leader companies are faring on their own pledges, by company and as a portfolio. Are they doing better than the governments that regulate them? Who are the leaders? Who are the laggards? Based on this analysis, we devise an engagement plan for the laggards.

A broad survey of where we are

Climate risks have taken precedence with the occurrence of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), held in Glasgow between 31st October and 13th November. This summit brought together almost 40,000 delegates, representing national, pan-national, corporate entities and of course Leonardo de Caprio, to accelerate global advancement toward the ambitions of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Climate Accords (COP21).

The UNFCCC is the international collaborative body established to stabilise greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”[2], within a timeframe that allows ecosystems to “adapt naturally to climate change, thereby protecting sustainable food production and economic development”[3].

The Paris Climate Accords is an international climate change treaty, adopted at COP21 in 2015 and ratified in 2016 by 196 UNFCCC parties. It formally acknowledged the need to scale the global response to climate change and formalised national ambitions to limit global warming to 2.0oC or ideally 1.5oC below pre-industrial levels[4].

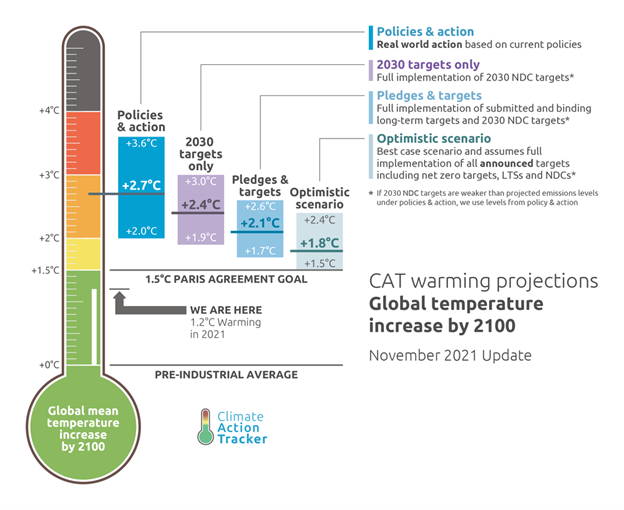

What is required

To achieve the 1.5oC scenario, global GHG emissions must peak by 2020, be reduced by at least 45% by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050 or soon after[5]. These goals necessitate the mobilisation of financial resources, new technology frameworks and enhanced capacity-building for the support of developing and vulnerable countries.

Global accountability is driven and monitored via an enhanced transparency framework which operates through “nationally determined contributions” (NDC)[6] submissions. These are a series of regular signatory disclosures which outline and communicate their recent climate actions. In order to ensure long term progression, the COP21 laid out a ‘ratchet’ mechanism by which every five years the signatories must lay out fresh commitments, which can then be used to determine whether the world is on track to achieve the long-term goals of the agreement.

What happened in Glasgow?

Recently the International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) report analysed the current NDCs and ascertained that unless there are “immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warmings to close to 1.5oC or even 2.0oC will be beyond reach”[7]. Consequentially, at COP26, several measures were announced:

| Coal and Fossil Fuels | Signatories committed to accelerating efforts towards the ‘phasing down’ of polluting fossil fuels such as unabated coal power. |

| Methane Pledge | 100 countries have committed to cutting emissions of methane, which is a potent GHG. |

| Climate Finance | ‘Rich countries’ signed a pledge to raise at least $100 billion per annum in climate finance and roughly $40 billion per annum for adaptation measures. |

| Carbon Markets | A new framework for a global carbon market was put into place under Article 6, which should function to facilitate better trading of carbon credits and improve the carbon offsetting system. |

| International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) | The IFRS Foundation trustees announced the creation of the ISSB Board, which will oversee the creation of a set of consistent standards for global ESG reporting which can be maintained through traditional assurance mechanisms. This should restrict green-washing trends by facilitating investor scrutiny of non-financial disclosures and allowing like-for-like comparisons between companies and their ESG efforts. |

| Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) | Mark Carney announced that over 450 financial firms, with US$130tn in assets, will join forces behind a common goal of steering the global economy towards the COP21 net-zero emission targets. Each member must commit to the science-based commitments to net-zero and aim to halve global emissions by 2030 and take part in the ‘Race to Zero’. |

These developments signify accelerating momentum of state, non-state, and subnational climate actions. However, there is currently little evidence of these ambitions and commitments translating into realised impact, highlighting a widening accountability gap between climate action commitment and resource deployment.

For example, the new UN Environment Programme report has noted that even if these new pledges and the 30+ new NDCs made before 2021 are carried out perfectly, warming over the 21st century is projected to be limited to 2.7oC, with a 66% probability and range of 2.2-3.1oC[8]. It concludes that “given the transparency of net-zero pledges, the absence of a reporting and verification system and the fact that few 2030 pledges put countries on a clear path to net-zero emissions, it remains uncertain if net-zero pledges is achievable”.

Consequences of global warming

The ramifications of a temperature rise this significant would be extreme. For example:

- The globe can expect 16 times more marine heatwaves each year at 1.5 degrees of warming. However, this figure rises to 23 and 41 times more at 2.0 and 3.5 degrees of warming respectively[10].

- Eight of the world’s 10 largest cities are costal and will face major flooding, erosion, and storm damages under even a 1.5oC temperature rise[11]. However, in a 3.0oC rise scenario, hundreds of millions of people would be displaced as a result of their residencies becoming uninhabitable due to sea-level rise[12].

- Habitat loss for all species would double or triple if temperature increases went from 1.5 degrees to 2 degrees. If the planet warms beyond 4.5 degrees, then the majority of the planet would no longer be able to host wildlife[13].

Thus, in addition to national procedures, corporate actors must also operate in good faith and pre-empt GHG reduction legislation to avoid contributing to substantial global harm.

Reassuringly, corporates with combined revenue of over U$13.1tn are currently pursuing net-zero emissions by the end of the century, aiming for a zero-carbon economy by 2050 via participation in the UN ‘Race to Zero’ campaign[14]. The current list of 1,541 signatories has grown from roughly 500 recorded in 2019[15].

However, within those commitments, the average percentage reduction for targets across all companies and timeframes is just under 40%. 33% of targets are short-term (between 2021-2025), 51% of targets are mid-term (2026- 2035), and only 15% of targets are long-term (post-2035)[16]. Whilst the number of commitments is encouraging, the lack of depth of the targets is concerning and does not indicate a clear strategy for these corporate actors achieving their long-term net-zero targets.

Despite this, Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) research shows that out of the organisations which are adequately disclosing their carbons status, over 80% are on track to meet their 2035 emission reductions targets[17]. Whilst there is variation across this pool of actors, these results suggest a correlation between willingness to publicise data and an ability to meet their goals. More importantly, progress towards short term targets should help actors to ensure successful and ambitious implementation of long-term mitigation ambitions.

Therefore, we can consider detailed public disclosures of carbon reduction targets and achievements as a rudimentary indicator of corporate GHG execution, thereby providing us with a vehicle for considering and engaging how Cerno portfolios are performing on these measures.

Cerno Global Leader companies – measuring commitments

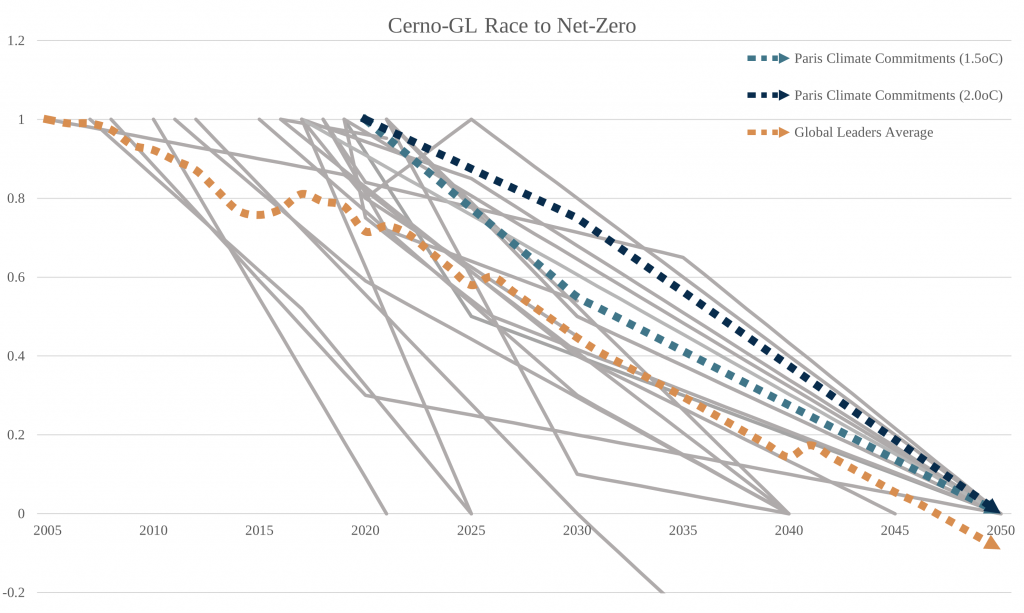

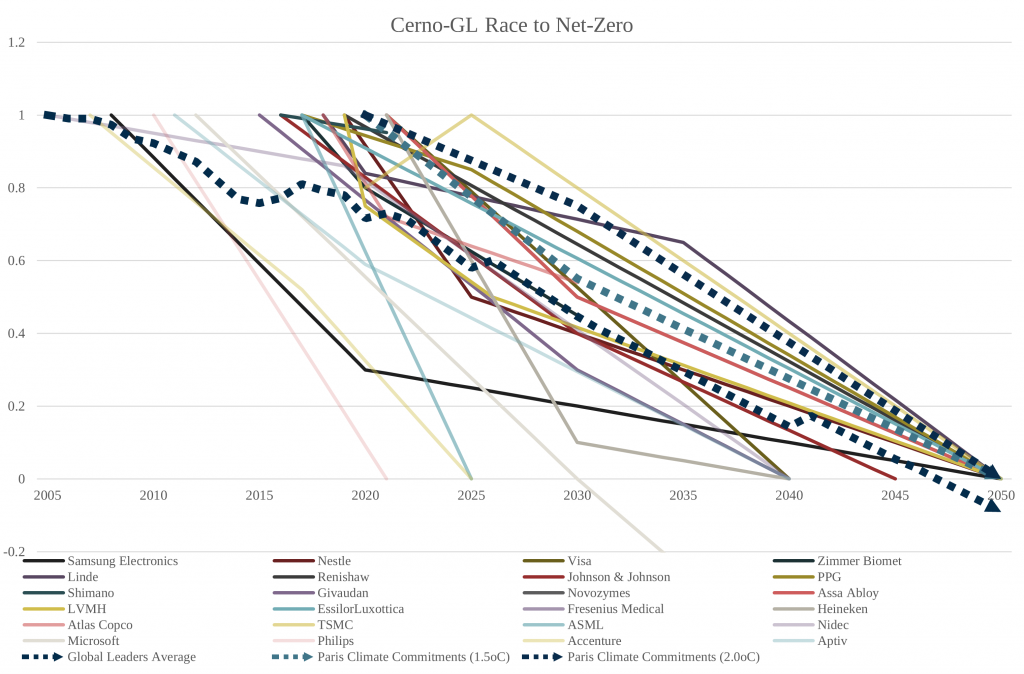

The two charts below owe a debt to Anthony Hene and his team at GMO who first displayed company tracks on carbon in this manner. We think this simple measure of display cannot be bettered so have adopted it.

The first chart displays commitments of all portfolio companies, indicated in grey to give an overall sense, with the average portfolio line in dotted blue. The second chart indicates each company’s name via a key.

Figure 1: Global Leaders Portfolio average targeted GHG reduction vs Paris Climate Requirements for 1.5oC & 2.0oC reduction scenarios

Figure 2: Global Leaders holdings targeted GHG reduction vs Paris Climate Requirements for 1.5oC & 2.0oC reduction scenarios

If we presume GHG reduction targets are generally accurate and reliable, we can state that the Global Leaders portfolio has and will likely continue to outperform GHG reduction targets required for both 1.5oC and 2.0oC warming avoidance pathways.

If these predictions are achieved, the Global Leaders portfolio will achieve a 55% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and net-zero by 2047, pre-empting the COP21 goal of ‘soon after 2050’.

Beyond net-zero

Furthermore, out of the 9 (37% of current) holdings that have committed to achieving net-zero emissions pre-2050, only Microsoft has specified its post-carbon-neutral GHG reduction plans. However, due to the notable commitment to sustainability and carbon reduction across the majority of the portfolio, it is reasonable to assume that they will also become not just net-zero but carbon negative further into the future. Therefore, the Global Leaders will likely become carbon neutral before the calculated 2047. However, we do not currently have enough data to reasonably estimate at what point.

This top-level analysis seems to indicate a level of success in our ability to select organisations which succeed in not only reacting to these high-pressure situations in a timely and responsible manner but also leading the globe in their innovations. This is commensurate with our signatory status within the UNPRI, which guides stewards of financial assets.

An additional contributor to this outperformance may be attributable to the positive influence of institutional activist owners.

Does an institutional share base promote better objectives and outcomes?

UBS Evidence Lab[18] recently conducted a piece of research that found correlations between the proportion of active institutional investors in an organisation, the underlying company’s performance in GHG reduction and their price per share. UBS found that the number of earnings calls that have mentioned ‘carbon’ over the last three years has tripled in number[19], demonstrating that the topic has become much more important to professional investors.

Organisations with the “strongest greening influence from their institutional shareholders in 2015 reduced their carbon intensity by a median of 18% over the following 5 years, compared to just 8% for companies with the weakest institutional influence”[20]. Consequentially, it stands to reason that an equity structure with a higher concentration of active institutional investors translates to higher shareholder carbon engagement, making it a greater priority for managers.

Moreover, UBS goes onto suggest that due to the continuing development of ‘carbon investing’, organisations that have succeeded in actively and publicly reducing their environmental impact eventually develop into what Goldman Sachs[21] terms ‘green-beneficiaries’ or even ‘greenablers’- organisations that benefit from and/or drive the transition towards a green economy. These corporates are more likely to benefit from the influx of green investors as the practice continues to bloom, via capital appreciation.

The UBS Evidence Lab also notes that eventually carbon investing will become mature, through all market participants gaining access to company carbon emissions data, which will drive equilibrium in the demand for low carbon investments.

Looking beyond carbon intensity as a measure

At that point, it is expected that carbon intensity will become less compelling as a forecaster of future outperformance, and instead become a potential risk signal with unexpected changes in carbon intensity correlating to carbon-centric investor sell-offs. Thus, it is likely that by identifying organisations that are less likely to suffer sudden volatility in the level of their carbon intensity, then we will be able to mitigate a future source of portfolio risk.

We suspect that as a portfolio that excludes carbon-based energy investments and focuses on market-leading corporates with sustainable competitive advantages, Global Leaders has benefited from this rise in institutional activism and will continue to benefit from its risk mitigation features.

Change is necessary

Whereas adaption is a key measure for us for investment, non-adaption would be the obvious corollary risk signal. In the words of Tomasi di Lampedusa, published in 1958, for everything to remain the same – in our case continued occupation of this planet – everything must change.

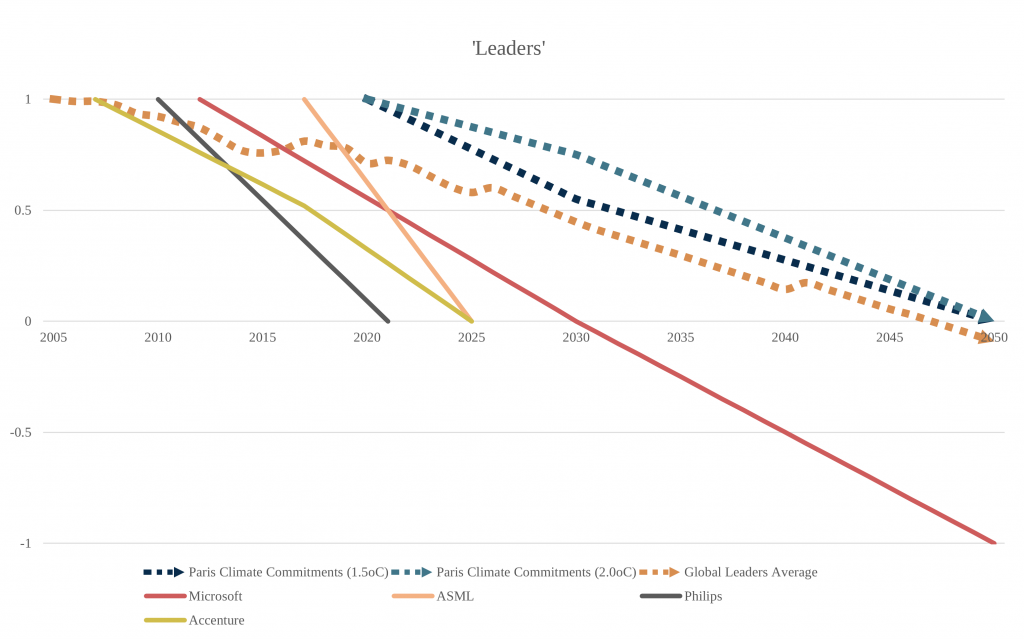

Clearly, much like the success of disclosing organisations with their targets, there is a level of variety within the Global Leaders portfolio, with some organisations such as Microsoft, Philips, Accenture and ASML appearing to lead the pack, whilst others such as Linde and TSMC appear to lag through their being slower to cut their scope 1 & 2 GHG emissions than required in the 2.00C scenario.

Figure 3: Accenture, ASML, Microsoft and Philips targeted GHG reduction vs Paris Climate Requirements for 1.5oC & 2.0oC reduction scenarios

Companies at the vanguard

The ‘leaders’ of the Global Leaders portfolio are ASML, Philips, Accenture and Microsoft. These holdings, on average, have committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2025, a full 25 years before COP21 goals.

Philips is now carbon neutral in its own operations, due to sourcing all electricity from 100% renewable sources and developing its green productions and solutions portfolio. As a result, Philips has reduced its carbon footprint on average by 10% per year, compared to relatively regular comparable sales growth in the same period[22].

Accenture has committed to achieving net-zero by 2025. This may seem less significant due to the relatively low carbon intensity of the organisation as a consultancy business. However, it is important to note that this will occur through absolute emission reductions via renewable energy implementation, supplier engagement, travel practice reviews and carbon inset investment in propriety, nature-based removal solutions[23]. Additionally, Accenture has also committed zero waste by 2025 and developing contingency plans for mitigating the impact of flooding and/or water scarcity in high-risk areas by 2025.

Similarly, ASML has ambitions to achieve net-zero emission across all operations by 2025 and reduce carbon emissions throughout the value chain. To do this, it has entered a contract with German energy firm RWE to purchase roughly 250GWh of green energy per year, in a 10-year power purchase agreement[24]. This will be supplied through two new onshore wind farms in the Netherlands, one offshore wind farm off Belgium and a solar power plant in the Netherlands[25].

The case of Microsoft

Finally, of note is Microsoft. Whilst they are the slowest of the ‘leaders’ to reach carbon neutrality, with a 2030 commitment, Microsoft is the only holding committed to continued GHG emission reduction post neutrality. By 2050, Microsoft has committed to removing enough carbon and carbon equivalents to be considered carbon neutral in operations, supply and value chain since being founded in 1975[26].

Microsoft has funded this initiative through an internal carbon fee which charges for direct, supply and value chain emissions. This year, Microsoft also introduced carbon reduction as an explicit aspect of their procurement process for their supply chain. Finally, they have committed to launching a US$1bn climate innovation fund and the use of their proprietary technology to aid global suppliers and customers in reducing their footprints. By 2050, this will cumulate in over 5 million tonnes of Carbon removal per annum[27].

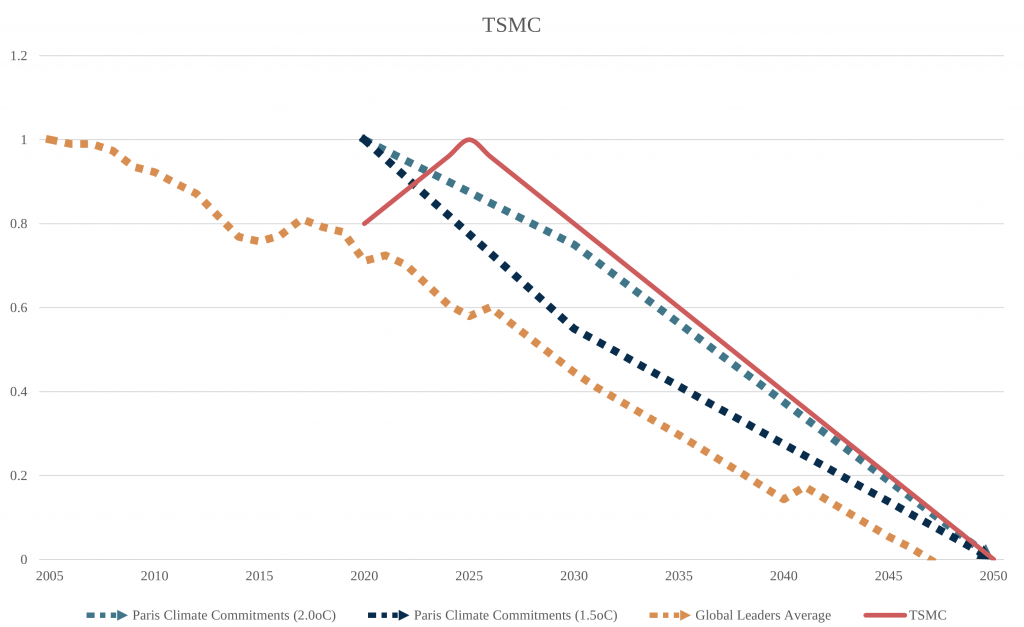

Figure 4: TSMC targeted GHG reduction vs Paris Climate Requirements for 1.5oC & 2.0oC reduction scenarios

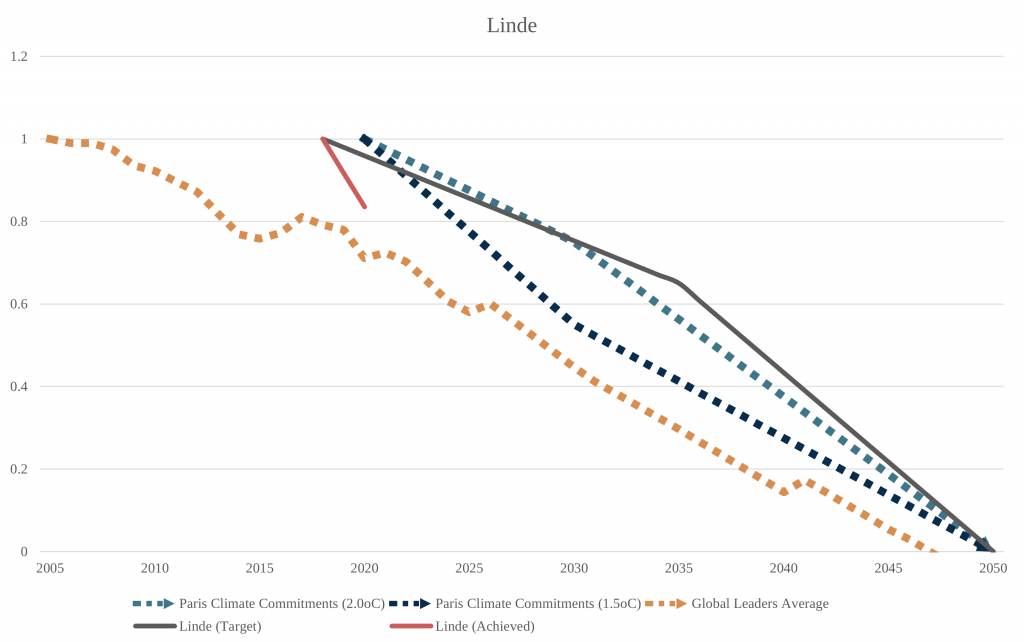

Figure 5: Linde achieved and targeted GHG reductions vs Paris Climate Requirements for 1.5oC & 2.0oC reduction scenarios

Looking at the laggards

We now address the holdings which appear to be laggards to the Paris Climate timeline. Whilst committed to net-zero by 2050, TSMC and Linde seem to lag the Paris GHG reduction timelines.

In September, TSMC committed to reaching net-zero by 2050. Chairman Mark Liu stated that ‘TSMC is deeply aware that climate change has a severe impact on the environment and humanity. As a world-leading semiconductor company, TSMC must shoulder its corporate responsibility to face the challenge of climate change’[28]. However, through setting a short-term goal of zero-emissions growth after 2025, they have been lagging the COP21 timeline. This is likely due to their needing to build capacity in the short term, with new factories being built in Japan, Arizona, and Taiwan.

However, it is key to note that TSMC functions within a carbon-intensive industry and is the first semiconductor company to join the RE100 (an initiative committing large-cap organizations to renewable electricity). Furthermore, TCFD has released a Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) report[29] , detailing risks and opportunities, as well as setting measurable benchmarks and targets.

Thus, TCFD is leading its industry by setting realistic targets, rather than committing to arbitrary dates with no ability to fulfil their goals.

On the other hand, Linde also operates within a carbon heavy industry. Similar to TSMC, its net-zero targets lag the Paris timeline. However, ongoing reductions have outpaced targets, with GHG intensity reduced by over 16% between 2018 and 2020[30].

Furthermore, despite its operational GHG intensity, Linde aims in the future to operate as a ‘greenabler’ and ‘green-beneficiary’[31], through its hydrogen business. They view blue and green liquid hydrogen as “carrying the hopes of a cleaner future”[32] through its potential as a realistic renewable fuel for commercial HGV and aviation vehicles. HGVs and aviation are responsible for 29.4% and 11.6% of transport CO2 emissions respectively[33][34], which in 2020 produced approximately 7.3 billion metric tons of GHG emissions. In comparison, Linde’s 2020 total carbon footprint in 2020 was 37.2 million tons of GHG[35]. Clearly, their ability to facilitate GHG reduction in their end-user is of much greater significance than their operational carbon.

Thus, an analysis of Linde and TSMC, which initially appear to be behind the curve, unveils the failings of top-down analysis, such as this. Simply examining scope 1&2 emissions reductions targets as a measure of environmental responsibility will often fail to consider the niches and complexities apparent on a company, industry, and country level.

Where disclosure could be improved

Consequentially, as some due diligence reveals our potential ‘laggards’ to be less of a portfolio drag than they might initially seem, our concern turns to those holdings within our portfolio in which carbon data disclosure is limited or non-existent. Within the Cerno Global Leader’s portfolio, these holdings are:

| Zimmer Biomet | Signatory of Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi), committed to reducing absolute scope 1 & 2 emissions 55% by 2030 from a 2017 baseline[36]. No current disclosure regarding net-zero timelines or targets. |

| Atlas Copco | Signatories of SBTi, committing to reduce absolute scope 1 & 2 GHG emissions 46% by 2030[37]. No current disclosure regarding net-zero timelines or targets. |

| Shimano | Committed to numerous ESG programs involving plastic and water waste reduction, and energy reduction[38]. As the largest global supplier of bicycle components, it facilitates global GHG reductions via an emissions-free form of transport. However, there has been minimal disclosure on operational, supply or value chain GHG emission reduction programs, or targets for alignment with COP21 goals. |

| Fresenius Medical | Has publicised a policy of regularly assessing its environmental impact and committing to developing appropriate environmental practices, programs and initiatives aimed at reducing their environmental footprint[39]. |

Out of these four holdings, Zimmer Biomet and Atlas Copco are of relatively little concern, due to their being signatories of the SBTi.

The SBTi is a partnership between the Customer Data Platform (CDP), UN Global Compact, World Resources Institute, and the Worldwide Fund for nature. SBTi summarises the latest client science and works with its signatories to respond appropriately through guidance on how much and how quickly they need to reduce their GHG emissions to prevent the worst effects of Climate change.

Thus, partnership companies such as Zimmer Biomet and Atlas Copco are setting short- and long-term emissions reduction targets in line with the latest climate science and are consequentially considered leaders within the industry. Clearly, as asset owners, we would prefer longer-term commitments to understand these organisations’ plans post-2030 emission reduction. However, as signatories, we feel confident that those plans will be in the process of being formulated and published in due course.

Engagement plan for Cerno Capital

Despite their relatively low GHG emission intensity, the holdings identified for further investigation are Shimano and Fresenius Medical, due to lack of GHG reduction targets or adequate disclosure of when such targets will be released or if they are being formulated.

Thus, moving forwards, our primary engagement plan will be as follows:

Firstly, we will engage with those organisations which lack a commitment to regular disclosures of carbon reduction. For Global Leaders, these two holdings are Shimano and Fresenius Medical. Our engagement will focus on understanding what GHG reduction efforts are ongoing, whether these programs are in line with regulations and our expectations and encourage the organisations to expedite better practices.

Secondly, we will engage with those organisations which have only short-term commitments and enquire about their long term GHG reduction plans. These holdings are Zimmer Biomet and Atlas Copco. However, their status as SBTi signatories may permit this engagement to be light.

Thirdly, we will engage with those 8 organisations which have committed to net-zero by 2050 but have not re-enforced their commitment by becoming signatories of the SBTi or alternative initiatives such as the UN Race to Zero Campaign. Signatory status will be strongly encouraged to facilitate the analysis of the announced GHG plans by experts with technical abilities.

Finally, we will engage with the remaining 12 organisations that have committed to long term net-zero plans which have been made in conjunction with SBTi signatory status. This engagement will focus on encouraging market-leading practices, such as plans for continued GHG reduction post-net-zero achievement and the reporting of larger data sets focused on absolute and scope 3 emissions.

—

[1] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf

[2] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-convention/what-is-the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change

[3] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-convention/what-is-the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change

[4] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

[5] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement/key-aspects-of-the-paris-agreement

[6] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs

[7] https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/

[8] https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/37350/AddEGR21.pdf

[9] https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/

[10] https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/the-difference-in-global-warming-levels-explained/

[11] https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

[12] https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/the-difference-in-global-warming-levels-explained/

[13] https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/the-difference-in-global-warming-levels-explained/

[14] http://datadrivenlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GlobalClimateAction2021_Final.pdf

[15] https://unfccc.int/news/commitments-to-net-zero-double-in-less-than-a-year

[16] http://datadrivenlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GlobalClimateAction2021_Final.pdf

[17] http://datadrivenlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GlobalClimateAction2021_Final.pdf

[18] UBS Global Research, ‘Q-Series Redux – Carbon Investing: How Can We Identify Greening Stocks?’, 16/11/2021

[19] UBS Global Research, ‘Q-Series Redux – Carbon Investing: How Can We Identify Greening Stocks?’, 16/11/2021

[20] UBS Global Research, ‘Q-Series Redux – Carbon Investing: How Can We Identify Greening Stocks?’, 16/11/2021

[21] Goldman Sachs Equity Research, ‘GS sustain – Investing in Green Capex: Themes and stocks to own’, 11/10/2021

[22] https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2020/20200225-philips-on-track-to-become-carbon-neutral-in-its-own-operations-this-year.html

[23] https://newsroom.accenture.com/news/accenture-sets-industry-leading-net-zero-waste-and-water-goals.htm

[24] https://www.futurenetzero.com/2021/02/11/dutch-firm-asml-inks-renewable-power-deal-with-rwe/

[25] https://www.futurenetzero.com/2021/02/11/dutch-firm-asml-inks-renewable-power-deal-with-rwe/

[26] https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2020/01/16/microsoft-will-be-carbon-negative-by-2030/

[27] https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2020/01/16/microsoft-will-be-carbon-negative-by-2030/

[28] https://www.reuters.com/technology/chipmaker-tsmc-aims-net-zero-emissions-by-2050-2021-09-16/

[29] https://esg.tsmc.com/download/file/TSMC_TCFD_Report_E.pdf

[30] https://www.linde-engineering.com/en/news_and_media/press_releases/news20210827.html

[31] Goldman Sachs Equity Research, ‘GS sustain – Investing in Green Capex: Themes and stocks to own’, 11/10/2021

[32] https://www.lindehydrogen.com/why-hydrogen

[33] https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/transport-sector-co2-emissions-by-mode-in-the-sustainable-development-scenario-2000-2030

[34] https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport

[35] https://www.linde-engineering.com/en/images/2020-sustainable-development-report_tcm19-609189.pdf

[36] https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/005/877/original/CDP_Science-Based_Targets_Campaign_-_2020_impact_report_spreads.pdf?1632754170

[37] https://www.atlascopcogroup.com/en/media/corporate-press-releases/2021/20211029-science-based-targets

[38] https://www.shimano.com/jp/img/pdf/esgsheet_en/esg_sheet_210209.pdf

[39] https://www.freseniusmedicalcare.com/fileadmin/data/com/pdf/About_us/Sustainability/Environment/CSR_Environment_Policy.pdf