By ION SIORAS

There has been much discussion in the financial and general press recently over Bitcoin’s recent price rally and what, if anything, it may indicate about Bitcoin’s ascendance as a possible store of value and means of exchange.

With respect to the former possibility, in some circles it has been forwarded as a potential replacement for gold in portfolios and – at the very least – having taken some shine off the value for gold since gold achieved its twelve-month peak at US$2,010/oz on 2nd August last year.

Bitcoin promoters harbour a dream bigger than this and some see it as an inevitably growing medium of exchange, partially displacing currencies.

Here we discuss Bitcoin from the technical standpoint and the resultant effects on market structure.

It is undoubtedly the case that bitcoin exhibits some pioneering concepts for any asset aiming to be a store of value and a means of exchange.

A decentralised ledger accessible by all for viewing and maintenance (the Bitcoin blockchain) makes the system both intrinsically resilient and equitable. The proof of work algorithm required to verify the validity of any transaction uses institutional grade cryptography (based on elliptic curves) to inspire total faith in the system, although questions have been raised about its longevity given the ascendance of quantum computing.

Finally the reward mechanism for dedicating computing resources (colloquially known as the mining of Bitcoin) ensures constant verification and a virtuous cycle of robustness as the network expands.

There are, though, some characteristics that can make it prone to instability and overshoots, namely fixed supply, concentration and low throughput. We deal with each in turn.

At the time of writing, with a price of US$54,726 per coin, the total capitalisation of Bitcoin is US$1.02tn. At its peak, it has risen nearly 18x from the December 2018 low, reminiscent of the 30x run it achieved in 14 months from October 2016 to its peak in December 2017.

One of the first points often noted by Bitcoin proponents is the inbuilt scarcity of Bitcoin. As per Satoshi Nakamoto’s original codebase for the Bitcoin blockchain, there can only be 21 million Bitcoins ever created.

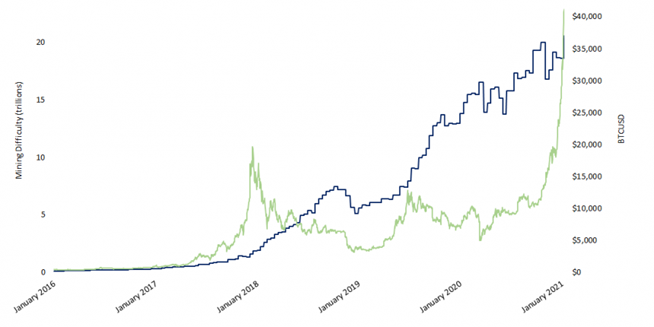

Of the 21 million coins, 18.6 million have already been mined (with a current mining rate of 6.25 bitcoins every 10 minutes). At current assumptions, the total stock is expected to be extracted by 2140, accounting for the exponential difficulty increase built into the system.

Bitcoin price vs computational mining difficulty, source : Coinbase

What is more interesting is that, of the 18.6 million coins currently mined, around 4 million have been “lost” (via forgotten pass keys and physically lost or destroyed hard drives holding bitcoin wallets), some irretrievably. This includes the roughly 1.1 million coins mined by Satoshi Nakamoto, which have remained dormant for over 10 years.

In equity markets there exists the concept of “float”, which is simply described as the net number of shares available for regular trading when removing closely held, largely immobile, holdings from the total share count.

History shows that low float stocks are prone to similar behaviour as demand and supply meets an artificially restricted pool of tradeable securities. At the extreme, low float stocks can undergo “squeezes” in price such as Volkswagen in 2008 briefly becoming the most valuable company in the world.

This concept of “float” can arguably be transposed to the supply of Bitcoin, where lost coins create an illusion of a much larger capitalisation than that which is truly accessible. Furthermore, the Bitcoin ecosystem exhibits high concentration. 150,000 addresses (0.42% of the total addresses) account for 85.6% of the total bitcoin supply available.

The reason for analysing market structure is that market prices are set at the margin. The entire “stock” of any asset or security is very rarely turned over with any regularity. The total value of any asset is therefore imputed from the market clearing price of a handful of transactions occurring at any point in time.

The truth of this can be observed in commodity markets, where physical and temporal constrains can result in extremes such as negative oil prices or squeezes in agricultural commodities due to price insensitive buying or selling at the margin.

Extending this to Bitcoin, we can connect the implied valuation of US$1tn+ for the entire supply with its trading volume characteristics (usually between 10% and 25% of total capitalisation) trading within a restricted float.

The impact of large buyers and sellers – dubbed “whales” in the bitcoin community – has a disproportionate impact on the price formation of an asset where marginal price setting is typically dominated by mainly retail participants on leverage.

As a result, the realised rolling 30 day volatility of Bitcoin often tracks above 100%, in comparison to the long run average of 18% for the S&P 500 or 8% for the Cerno Select strategy.

The applicability of concepts such as float and commodity market dynamics to Bitcoin make it more reminiscent to an asset or commodity, possibly digital gold being the closest analogy, than to a currency.

That being the case, we should also note that Bitcoin exhibits significant resource demands for extraction, just as physical commodities do. Current estimates for the power consumption required for network functioning and the “mining” of new Bitcoin is 78 TWh, roughly equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of Chile or Argentina or the Netherlands.

Popular with the young and dismissed by the old, we should probably recognise Bitcoin as a financial analogue of some of the factional pressures within society.

For some traders, Bitcoin is a “cool” way to make money. The original band of cyber-punks who supported it are seeking thesis confirmation. Elon Musk is keen and has put his corporate treasury into it. To this group we should add criminals, large and small, for whom it provides anonymity for illicit transactions on the dark web and elsewhere.

On the “other side of the coin”, Bitcoin represents a dull, throbbing headache for market regulators and Central Banks.

Bitcoin faces challenges in the path to wider acceptance. It may be outlawed in more countries and this could hasten moves to establish Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). For the time being, Bitcoin remains a speculation that will be happy for some and quite miserable for others. No financial Nirvana, then.